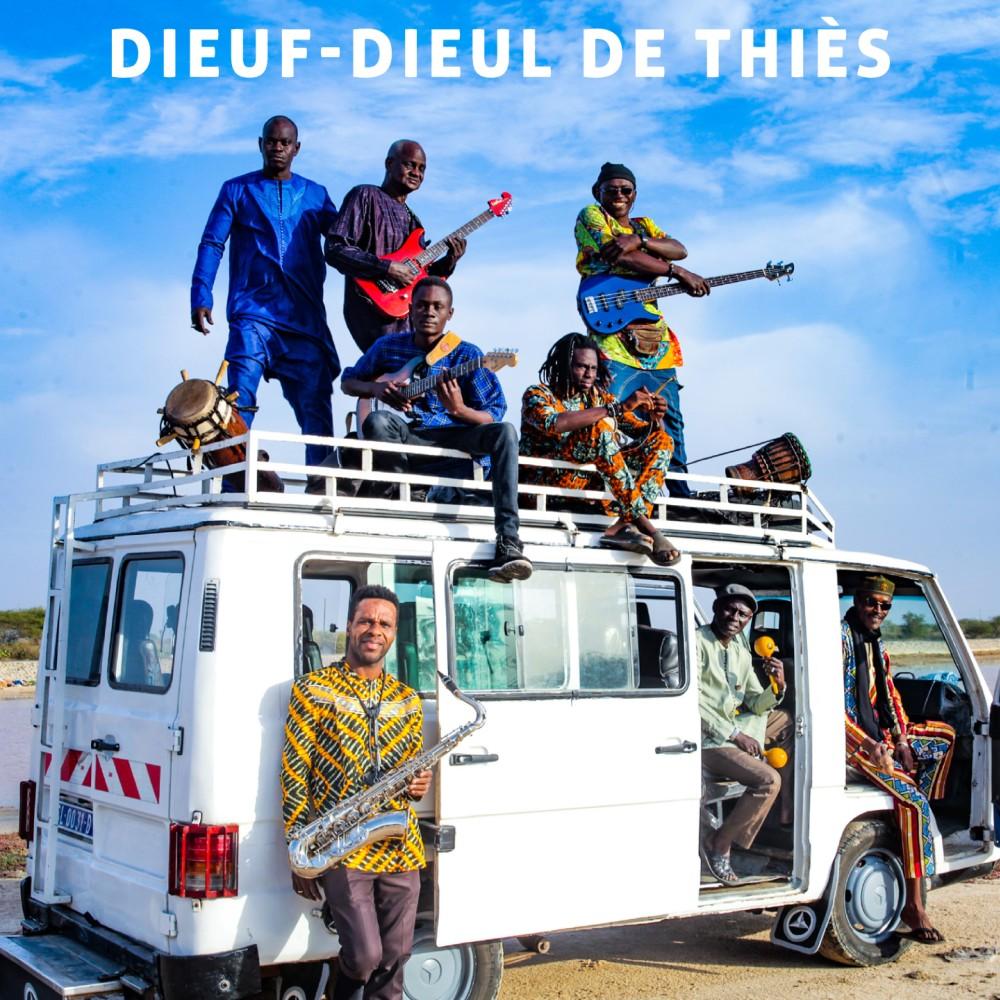

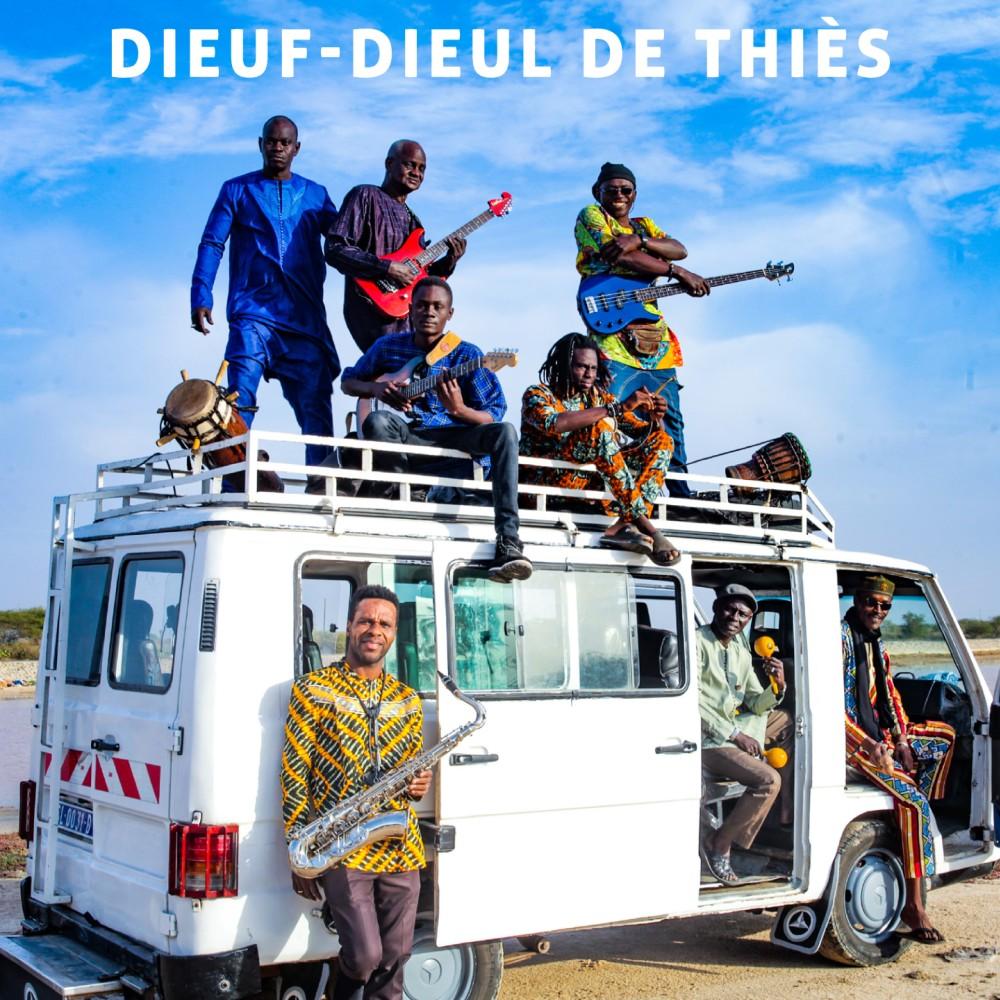

"Patience knows no time", according to a Senegalese proverb. There is no better way to describe the destiny of Dieuf Dieul de Thiès, finally releasing their first real album more than forty years after the event.

It all started in 1979 when the well-known Rufisque-based band Ouza et ses Ouzettes came to play at the Gandiol in Thiès, a major city located an hour away from the capital, and some members decided to leave the group. They soon crossed paths with a small group of young people, some of them still at school, all of them equally passionate about music. Among them, Bass Sarr remembers: "We rehearsed every day, they came to support us, and we in turn worked on their repertoire. That's how we decided to join forces. That allowed them to stay in Thiès.” And it allowed all of them to begin the adventure of this group. The only thing left to do was choose a name: after thirty minutes over tea, their instruments set aside, they agreed on Dieuf Dieul, a phrase referring to the mouridism preached at the beginning of the twentieth century by Sheikh Ibrahim Fall, that could be translated as "Give — Receive". In other words: "You reap what you sow".

For sure, but they still had to dig the fertile furrow in which their originality would thrive. Through a contact at the city hall, they immediately got a booking at the Gorom, a very popular nightclub in Thiès. The manager, Madame Diop, took them for one Saturday night, just to try. Trial successful, they took up residence there, in every sense of the word: some of the members were housed there, rehearsing on the premises, and Dieuf Dieul played every week. This is how the group began to get talked about in the city, all the more so when Gora Mbaye, a famous griot from Thiès who played in the traditional ensemble of Thiès, joined them and brought in a lot of people including the political and musical elite. The front man was guitarist Pape Seck who, even while playing with Ouza, had already distinguished himself in the mythical Guelewar, a psychedelic combo from Banjul, Gambia. It happened to be there, and in the nearby Casamance region, that Dieuf Dieul went on tour. While staying in Kolda the group crossed paths with singer Assane Camara, nicknamed "Kamouyandé", an expert in the local version of rumba, who quickly joined the group. During this fertile period, two records — the only two audible traces — were recorded by Moussa Diallo in Sangomar, in Casamance. Three decades later, in 2013 and 2015, they would be brought out of the oblivion of history on Teranga Beat, the label founded by the indefatigable sound collector Adamantios Kafetzis.

The formula developed on Volumes 1 and 2 of Aw Sa Yone testifies to the uniqueness of this multi-influenced group, mixing all the local musics with the Afro-diasporic idioms that dominated the international scene at the time, reflecting the great variety of their ethnic origins. A veritable funky swirl of total Mandingo guitars, super soulful brass, Latin rock rhythms, with voices planted on top, at the dawn of the 1980s the Dieuf-Dieul of Thiès seemed poised to be a potential rival to the brilliant Super Etoile of Dakar. History chose the latter, which included the future king of m'balax: Youssou N'Dour. “Our music was a symbiosis of the ethnic groups that make up our society: it was a mixture of Afro-Mandingo sounds, the kora masters and more American music. We didn't want to play just the local m’balax,” insisted Pape Seck in 2016, 64 years old and still riding high as he prepared his first comeback with other living veterans, rehearsing intensely in the Dakar medina and even performing at Ravin, a large nightclub in Pikine. Next to him, the singer Bass Sarr continued: “At the time, a producer wanted to promote us, because we were making quite a lot of noise! But they put obstacles in our way: we shouldn't uproot those who had been planted. The Number One, the Diamono, the Baobab, all that…”

They gave their music a name, afro-mandingo, a Latin afro-jazz tendency permeated with blasting electric guitars and churning percussion, mixing modern and older cultures and music. “Rhythmically, it was very different from what was played in Dakar, and when we came back to the capital the public was curious to hear us. We even competed with Youssou n’Dour,” recalled Bass Sarr, the only surviving founding member, in January 2023. Unfortunately, the story ended there for Dieuf-Dieul, which began to experience internal dissent as early as 1983, following its initial acclaim. “Other bands came looking for musicians, starting with Pape Seck who was poached by Baaba Maal, a fan of the group.”The loss of their leader, main composer and chief arranger would prove fatal for the group, which continued for two years under various configurations before splitting up without releasing a record — only a cassette was released under the radar — or even having had the chance to tour abroad.

This was how things stood in 2017, when the reformed and reformed band started touring Europe under the impulse of WAX Booking, seducing a new audience in France as well as in the Netherlands. “Playing in front of Europeans is more rewarding because they are more attentive to our music, which is not simple m'balax. That's probably why we're not often asked on stage in Senegal,” Bass Sarr continues, not without a touch of irony. It was in December 2019 at the French Institute in Saint Louis that they recorded this “new” record, using analogue equipment, more than 160 kilos of material (tube microphones, old-fashioned mixing desk) brought in from France with Sylvain Dartoy from WAX Booking and Christian Hierro from Back to Mono. Based on live recordings for the rhythm section, on which the vocals and horns were recorded in their own booths, this recording opts for a warm sound, like in the good old days. And it’s all the better for it.

Only Pape Seck, who died in 2022, and Bass Sarr remained from the original line-up, even if Kamouyandé left them a final composition before his death, one month before the recording. Alongside them, a new team of younger musicians, from Thiès as well as Dakar, all of them in tune with the original sound of Dieuf-Dieul. They cover some of their “classics”, rearranged for the occasion, including the favourites Na Binta and Ariyo, but also Djirim, a ballad that flirts with added reggae rhyddims. New compositions are added, often conceived together, except for Dieuf Dieul Ca Kanam which bears the signature of Bass Saar. This title, which its author translates as “Push on further, the Dieuf Dieul is not finished", is emblematic of an approach that follows in the deep furrow sown by the elders, while at the same time putting some stitches into a history strewn with memory gaps. “In forty years, Senegalese society has changed a lot. Young people are much more committed, here and even abroad. But at the same time, social relations are more difficult, unemployment is constant, people don’t help each other any more, it’s the age of every man for himself. The days of Senegal as a land of teranga are long gone.” True, but perhaps there is still time to listen to them and rediscover this sense of good hospitality...

Jacques Denis (English translation: Roger Surridge)